The history of agriculture records the domestication of plants and animals and the development and dissemination of techniques for raising them productively. Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of . At taxa least eleven separate regions of the Old and New world were involved as independent centre of origin.

The history of agriculture records the domestication of plants and animals and the development and dissemination of techniques for raising them productively. Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of . At taxa least eleven separate regions of the Old and New world were involved as independent centre of origin.

Wild grains were collected and eaten from at least 105,000 years ago. However, domestication did not occur until much later. Starting from around 9500 BC, the eight Neolithic founder crops – emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas, and flax – were cultivated in the Levant. Rye may have been cultivated earlier, but this remains controversial. Rice was domesticated in China by 6200 BC with earliest known cultivation from 5700 BC, followed by mung, soy and azuki beans. Pigs were domesticated in Mesopotamia around 11,000 BC, followed by sheep between 11,000 BC and 9000 BC. Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan around 8500 BC. Sugarcane and some root vegetables were domesticated in New Guinea around 7000 BC. Sorghum was domesticated in the Sahel region of Africa by 3000 BC. In the Andes of South America, the potato was domesticated between 8000 BC and 5000 BC, along with beans, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs. Bananas were cultivated and hybridized in the same period in Papua New Guinea. In Mesoamerica, wild teosinte was domesticated to maize by 4000 BC. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 3600 BC. Camels were domesticated late, perhaps around 3000 BC.

The Bronze Age, from c. 3300 BC, witnessed the intensification of agriculture in civilizations such as Mesopotamian Sumer, ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilisation of the Indian subcontinent, ancient China, and ancient Greece. During the Iron Age and era of classical antiquity, the expansion of ancient Rome, both the Republic and then the Empire, throughout the ancient Mediterranean and Western Europe built upon existing systems of agriculture while also establishing the manorial system that became a bedrock of medieval agriculture. In the Middle Ages, both in the Islamic world and in Europe, agriculture was transformed with improved techniques and the diffusion of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton and fruit trees such as the orange to Europe by way of Al-Andalus. After the voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1492, the Columbian exchange brought New World crops such as maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe, and Old World crops such as wheat, barley, rice, and turnips, and livestock including horses, cattle, sheep, and goats to the Americas.

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers were introduced soon after the Neolithic Revolution and developed much further in the past 200 years, starting with the British Agricultural Revolution. Since 1900, agriculture in the developed nations, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, has seen large rises in productivity as human labour has been replaced by mechanization, and assisted by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding. The Haber-Bosch process allowed the synthesis of ammonium nitrate fertilizer on an industrial scale, greatly increasing crop yields. Modern agriculture has raised social, political, and environmental issues including overpopulation, water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs and farm subsidies. In response, organic farming developed in the twentieth century as an alternative to the use of synthetic pesticides.

Origin hypotheses

Scholars have developed a number of hypotheses to explain the historical origins of agriculture. Studies of the transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies indicate an antecedent period of intensification and increasing sedentism; examples are the Natufian culture in the Levant, and the Early Chinese Neolithic in China. Current models indicate that wild stands that had been harvested previously started to be planted, but were not immediately domesticated.

Localised climate change is the favoured explanation for the origins of agriculture in the Levant. When major climate change took place after the last ice age (c. 11,000 BC), much of the earth became subject to long dry seasons .These conditions favoured annual plants which die off in the long dry season, leaving a dormant seed or tuber. An abundance of readily storable wild grains and pulses enabled hunter-gatherers in some areas to form the first settled villages at this time.

Early development

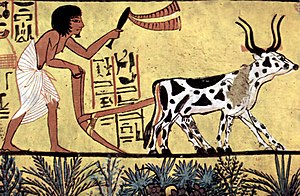

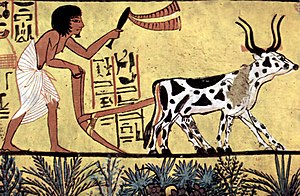

Sumerian harvester's sickle, 3000 BC, made from baked clay Early people began altering communities of flora and fauna for their own benefit through means such as fire-stick farming and forest gardening very early. Wild grains have been collected and eaten from at least 105,000 years ago, and possibly much longer. Exact dates are hard to determine, as people collected and ate seeds before domesticating them, and plant characteristics may have changed during this period without human selection. An example is the semi-tough rachis and larger seeds of cereals from just after the Younger Dryas (about 9500 BC) in the early Holocene in the Levant region of the Fertile Crescent. Monophyletic characteristics were attained without any human intervention, implying that apparent domestication of the cereal rachis could have occurred quite naturally.

An Indian farmer with a rock-weighted scratch plough pulled by two oxen. Similar ploughs were used throughout antiquity. Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least 11 separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin.[14] Some of the earliest known domestications were of animals. Domestic pigs had multiple centres of origin in Eurasia, including Europe, East Asia and Southwest Asia, where wild boar were first domesticated about 10,500 years ago. Sheep were domesticated in Mesopotamia between 11,000 BC and 9000 BC.Cattle were domesticated from the wild aurochs in the areas of modern Turkey and Pakistan around 8500 BC. Camels were domesticated late, perhaps around 3000 BC.

It was not until after 9500 BC that the eight so-called founder crops of agriculture appear: first emmer and einkorn wheat, then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas and flax. These eight crops occur more or less simultaneously on Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) sites in the Levant, although wheat was the first to be grown and harvested on a significant scale. At around the same time (9400 BC), parthenocarpic fig trees were domesticated.

Domesticated rye occurs in small quantities at some Neolithic sites in (Asia Minor) Turkey, such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (c. 7600 – c. 6000 BC) Can Hasan III near Çatalhöyük, but is otherwise absent until the Bronze Age of central Europe, c. 1800–1500 BC.[24] Claims of much earlier cultivation of rye, at the Epipalaeolithic site of Tell Abu Hureyra in the Euphrates valley of northern Syria, remain controversial. Critics point to inconsistencies in the radiocarbon dates, and identifications based solely on grain, rather than on chaff.

By 8000 BC, farming was entrenched on the banks of the Nile. About this time, agriculture was developed independently in the Far East, probably in China, with rice rather than wheat as the primary crop. Maize was domesticated from the wild grass teosinte in West Mexico by 6700 BC. The potato (8000 BC), tomato, pepper (4000 BC), squash (8000 BC) and several varieties of bean (8000 BC onwards) were domesticated in the New World.

Agriculture was independently developed on the island of New Guinea. Banana cultivation of Musa acuminata, including hybridization, dates back to 5000 BC, and possibly to 8000 BC, in Papua New Guinea.

Bees were kept for honey in the Middle East around 7000 BC.Archaeological evidence from various sites on the Iberian peninsula suggest the domestication of plants and animals between 6000 and 4500 BC. Céide Fields in Ireland, consisting of extensive tracts of land enclosed by stone walls, date to 3500 BC and are the oldest known field systems in the world. The horse was domesticated in the Pontic steppe around 4000 BC. In Siberia, Cannabis was in use in China in Neolithic times and may have been domesticated there; it was in use both as a fibre for ropemaking and as a medicine in Ancient Egypt by about 2350 BC.

Clay and wood model of a bull cart carrying farm produce in large pots, Mohenjo-daro. The site was abandoned in the 19th century BC. In northern China, millet was domesticated by early Sino-Tibetan speakers at around 8000 to 6000 BC, becoming the main crop of the Yellow River basin by 5500 BC. They were followed by mung, soy and azuki beans.

In southern China, rice was domesticated in the Yangtze River basin at around 11,500 to 6200 BC, along with the development of wetland agriculture, by early Austronesian and Hmong-Mien-speakers. Other food plants were also harvested, including acorns, water chestnuts, and foxnuts. Rice cultivation was later spread to Island Southeast Asia by the Austronesian expansion, starting at around 3,500 to 2,000 BC. This migration event also saw the introduction of cultivated and domesticated food plants from Taiwan, Island Southeast Asia, and New Guinea into the Pacific Islands as canoe plants. Contact with Sri Lanka and Southern India by Austronesian sailors also led to an exchange of food plants which later became the origin of the valuable spice trade. In the 1st millennium AD, Austronesian sailors also settled Madagascar and the Comoros, bringing Southeast Asian and South Asian food plants with them to the East African coast, including bananas and rice. Rice was also spread southwards into Mainland Southeast Asia by around 2000 to 1500 BC by the migrations of the early Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai-speakers.

In the Sahel region of Africa, sorghum was domesticated by 3000 BC in Sudan and pearl millet by 2500 BC in Mali. Kola nut and coffee were also domesticated in Africa. In New Guinea, ancient Papuan peoples began practicing agriculture around 7000 BC, domesticating sugarcane and taro. In the Indus Valley from the eighth millennium BC onwards at Mehrgarh, 2-row and 6-row barley were cultivated, along with einkorn, emmer, and durum wheats, and dates. In the earliest levels of Merhgarh, wild game such as gazelle, swamp deer, blackbuck, chital, wild ass, wild goat, wild sheep, boar, and nilgai were all hunted for food. These are successively replaced by domesticated sheep, goats, and humped zebu cattle by the fifth millennium BC, indicating the gradual transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture.

Maize and squash were domesticated in Mesoamerica; potato in South America, and sunflower in the Eastern Woodlands of North America.

Civilizations

Sumer

Sumerian farmers grew the cereals barley and wheat, starting to live in villages from about 8000 BC. Given the low rainfall of the region, agriculture relied on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Irrigation canals leading from the rivers permitted the growth of cereals in large enough quantities to support cities. The first ploughs appear in pictographs from Uruk around 3000 BC; seed-ploughs that funneled seed into the ploughed furrow appear on seals around 2300 BC. Vegetable crops included chickpeas, lentils, peas, beans, onions, garlic, lettuce, leeks and mustard. They grew fruits including dates, grapes, apples, melons, and figs. Alongside their farming, Sumerians also caught fish and hunted fowl and gazelle. The meat of sheep, goats, cows and poultry was eaten, mainly by the elite. Fish was preserved by drying, salting and smoking.

The GREEN REVOLUTION also called third

agricultural Revolution That is a set of research technology transfer

initiatives occurred between 1950s to 1960s ,that increased agricultural

throughout the world, beginning mainly from late 1960s ,that

the initiatives resulted in the adoption

of new technologies such as high yielding varieties (HYVs) of cereals ,mainly dwarf wheat

and rice. It was associated with chemical

fertilizers, agrochemicals ,and controlled water supply (usually

involving irrigation ) and new

methods of cultivation ,

including mechanization .These all were seen as “package of practices ” to supersede ‘ traditional’

technology and to